Dear Readers:

Thermidor, followed by Bonapartism

Continuing to work through this essay by publicist Vladimir Mozhegov. Mozhegov describes cultural and intellectual processes occuring in the Soviet Union in the 1930’s. Yesterday we talked about the concept of “Thermidor”, and I should have been more careful to specify the difference between Mozhegov’s words, which I take as a starting point; and my own thoughts and opinions. Mozhegov did not mention the word “Thermidor”, that was me. “Thermidor” is shorthand for the counter-revolutionary processes which follow any revolution. It’s a normal phenomenon: In life, as in physics, every action is followed by a reaction. Sometimes the reaction is massive; sometimes it is simply a course correction.

In Soviet terms, “Thermidor”, as commenter Lyttenburgh pointed out, can be thought of as beginning very early in the game, while Lenin was still alive, with the implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP). This, in itself, was a retreat (which Lenin openly admitted) from the economic principles of communism. Still, this was a mild form of Thermidor, not like the original French one, when revolutionary leaders such as Robespierre were arrested and executed. That never happened to Lenin. Although it did happen to most of Lenin’s peers roughly a decade later.

With that out of the way, let us return to Mozhegov, and the key point of his essay, which attempts to answer the question: “Why was Stalin so jonesy for the Russian poet Pushkin?”

Are Marxists Supposed To Hate Bourgeois Culture?

If you recall, Mozhegov writes that the mid-1930’s were a time when the Russian government went all out with the notion of “culture” and in particular the glorious Russian culture. Mozhegov claims that the very idea of the Russian national culture became the foundation on which socialist transformations were to take place.

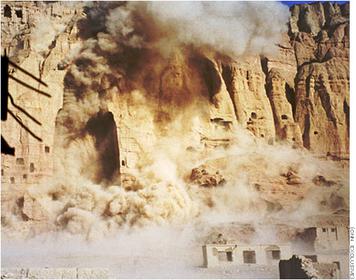

In Afghanistan, Taliban shows how they value classical culture.

Remember (and this is yalensis speaking now): Every action is followed by a reaction. And every reaction is followed by a reaction to that reaction. The Communist Party under Stalin launched a very ambitious program to completely transform Russia and the other Soviet republics: vast agricultural reforms, industrialization, a beefing up of the defense capabilities in preparation for the inevitable war.

All of this is fact. But is Mozhegov correct that culture (and specifically, Russian national culture) needed to be brought into harness for this effort? And even if this were true, was it such a bad thing? Personally, I believe that the Stalinist emphasis on culture was a good thing. Imagine the opposite: What if the Bolsheviks had been iconoclasts, like the Taliban? What if they had burned down all the libraries and the classical ballet theaters, on the grounds that all this great culture was just Tsarist propaganda?

“Culture,” Mozhegov writes, “and specifically Russian national culture, factually was placed into the very center of the socialist transformations which were taking place. Which, from the point of view of Marxism, is absolute nonsense.”

Schoolboy Pushkin: Aristo jerk?

Perhaps Mozhegov means, that real Marxists, on coming to power, would scrap all the old culture of whatever country they lived in, and create a culture based on something completely new. Like what, the mind boggles? Socialistic break-dancing? A new type of proletarian finger-painting?

“After all,” Mozhegov writes, “so-called scientific Marxism rejects culture, all the more so the culture of preceding formations which belonged to extinct classes. From the point of view of orthodox Marxism, Pushkin was an element of the bourgeois-aristocratic world, and as such he needed to be pushed aside.”

Er, no…. Personally I think Mozhegov needs to brush up on his Marxist reading list. Every major Marxist intellectual, starting with Marx himself, valued what was best in bourgeois and even pre-bourgeois culture. Marxists read books, visit the theater, go to the museums. Probably more so than ordinary non-Marxist average joes who are only interested in hooligan pursuits such as football and cockfighting.

Was Pushkin Really All That Great?

Mozhegov goes on to diss Pushkin as something highly over-rated, even in his time: “In the 19th century Pushkin was the poet of a strictly intellectual elite, the poet of individuals of an aristocratic spirit. Pushkin was not even mentioned in the reading list of the revolutionary intelligentsia. The latter considered him to be something distant, not very weighty; someone with his head in the clouds and removed from the needs of the people.”

“Personally, I prefer Karamzin.” Left to right: Lunacharsky, Lenin, Trotsky

The decision to erect Pushkin on the Soviet Mount Olympus was made by Stalin. Following on Pushkin’s coat-tails, also a few other pre-revolutionary types were partially rehabilitated; for example, Dostoevsky and some of the Symbolists. Writers who had been previously rejected by the generation of revolutionary intellectuals.

In turn, Stalin’s decision to place Pushkin up on the pantheon was influenced by Bolshevik intellectual Anatoly Lunacharsky, whom we briefly mentioned yesterday.

Mach Macht Recht

Lunacharsky was born in 1875 in Poltava, Ukraine, part of the Russian Empire at that time. He converted to Marxism at the age of 15 and studied at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. (Switzerland at that time having a sort of “madrasas” system for churning out Russian revolutionaries, as commenter Lyttenburgh has noted!) Lunacharsky met many interesting socialist leaders of that era, including German-Jewish firebrand Rosa Luxemburg. Lunacharsky joined the Russian Social-Democratic Party (which was the Russian branch of the Second International), and when the party split into two factions in 1903, Bolsheviks vs Mensheviks, he sided with the former.

Internal faction-fighting continued to split the Bolshevik faction into sub-factions. One of the fights pitted Lenin against Alexander Bogdanov. Readers might recall that we talked about Bogdanov and his experiments in blood transfusions, in my earlier series about Lenin’s mummification. But that was to come much later, we’re still back in 1907. In those heady but innocent years, Bogdanov locked horns with Lenin over a vital political issue. Did this concern German foreign policy? Or the Bolshevik position on unrest in the Balkans? Or perhaps tactical differences over trade union organizing?

Internal faction-fighting continued to split the Bolshevik faction into sub-factions. One of the fights pitted Lenin against Alexander Bogdanov. Readers might recall that we talked about Bogdanov and his experiments in blood transfusions, in my earlier series about Lenin’s mummification. But that was to come much later, we’re still back in 1907. In those heady but innocent years, Bogdanov locked horns with Lenin over a vital political issue. Did this concern German foreign policy? Or the Bolshevik position on unrest in the Balkans? Or perhaps tactical differences over trade union organizing?

No… not exactly. The big factional dispute concerned something called empirio-criticist philosophy, which was being promoted by a German philosopher named Ernst Mach. Mach’s supporters were called Machians. Bogdanov along with his friend and roommate Lunacharsky, became Machian supporters. Lenin was opposed to Mach. Machian philosophy made Lenin very cranky. This was the essence of the bitter factional dispute.

The Great War: Was it just a bad dream?

I know, I know, this all sounds highly ludicrous. Why fight and split a political party over an obscure point of philosophy? Because it seemed very important at the time, that’s why. Lenin felt that the Machians were verging dangerously close to Berkelian Idealism, to the notion that there is actually no material world. No, this life we live and everything we see around us is all just a bad dream!

Materialism is the heart of Marxism. Without a “belief” in the materiality of our universe, then there is no future for the proletariat and, by extension, for humanity itself. QED!

Bottom line: Lunacharsky took Bogdanov’s side against Lenin in that particular faction fight. Feelings were hurt. Friends became enemies. Then five years go by and it’s World War I. Everybody comes back together. Old grievances and hurts are forgotten. And sure enough, Lunacharsky took the “correct” position about the war: The same position that Calvin Coolidge allegedly took about sin: He was against it. Luncharsky and Lenin kissed and made up. All good friends again, and united by anti-war fervor. Subsequently, Lunacharsky played a key role in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and soon became the Minister of Culture in the new government.

And now we skip forward another 20 years, and we are back where we started: With Stalin in firm control of both Party and State. And Lunacharsky urging Stalin to show a lot of respect for Alexander Pushkin.

[to be continued]